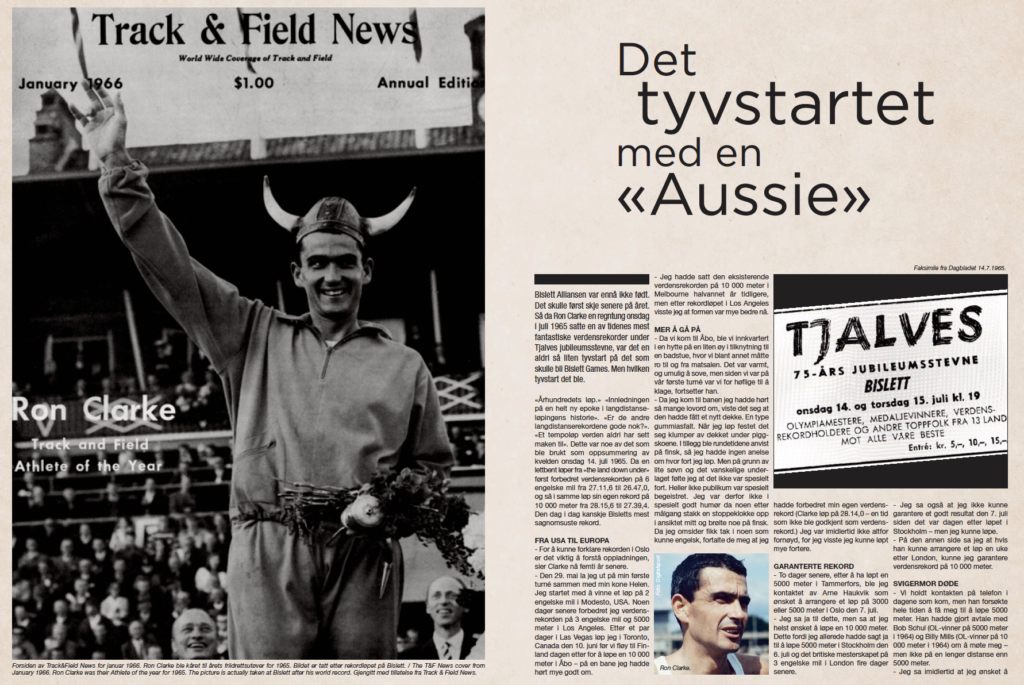

The Bislett Alliance had not yet been born. That would only happen later in the year. So, when Ron Clarke, on a rain-soaked Wednesday in July 1965, set one of the most astonishing world records of all time at Tjalve’s anniversary meet, it was a small “false start” to what would later become the Bislett Games. But what a false start it was.

This interview was previously published in the anniversary book marking the first 50 years of the Bislett Games, released in 2015. But it is the first time it has been published in English.

“Race of the century.”

“The beginning of a completely new era in the history of long-distance running.”

“Are the other long-distance records good enough?”

“A paced race the world has never seen the like of.”

These were some of the descriptions used to sum up the evening of Wednesday, 14 July 1965.

A light-footed runner from “the land down under” first improved the world record for six miles from 27:11.6 to 26:47.0, and then, in the same race, his own world record for 10,000 metres from 28:15.6 to 27:39.4.

To this day, it is perhaps the most legendary record ever set at Bislett.

From the USA to Europe

– To understand the record in Oslo, it’s important to understand the build-up, Clarke said when we interviewed him for the 50-year anniversary book of the Bislett Games in 2015.

Clarke passed away on 17 June that same year, aged 78.

On 29 May, I set off on my first tour together with my wife, Helen. I started by winning a two-mile race in Modesto, USA. A few days later, I broke the world records for three miles and 5,000 metres in Los Angeles. After a couple of days in Las Vegas, I ran in Toronto, Canada, on 10 June, before we flew to Finland the next day to run 10,000 metres in Turku – on a track I had heard a lot of good things about.

– I had set the existing world record for 10,000 metres in Melbourne a year and a half earlier, but after the record race in Los Angeles, I knew my form was much better now.”

More in Reserve

– When we arrived in Turku, we were accommodated in a cabin on a small island connected to a sauna, where we even had to row to and from the dining hall. It was hot and impossible to sleep, but since this was our first tour, we were too polite to complain, he continued.

– When I finally got to the track I’d heard so many glowing reviews about, it turned out it had been given a new surface – a kind of rubberised asphalt. As I ran, clumps of the surface stuck to the spikes on my shoes.

– On top of that, lap times were called out in Finnish, so I had no idea how fast I was running. Because of the lack of sleep and the difficult surface, I felt I wasn’t going particularly fast. The crowd wasn’t especially enthusiastic either. So, I wasn’t in the best of moods when, after finishing, someone shoved a stopwatch in my face and shouted something in Finnish.

– When I finally found someone who spoke English, they told me I had broken my own world record (Clarke ran 28:14.0 a time that was not ratified as a world record.)

– I still wasn’t particularly happy, because I knew I could have run much faster.

Guaranteed Record

– Two days later, after running 5,000 metres in Tampere, I was contacted by Arne Haukvik, who wanted to arrange a 3,000 or 5,000 metres race in Oslo on 7 July.

– I agreed but said I would much rather run a 10,000 metres. That was because I had already agreed to run a 5,000 metres in Stockholm on 6 July and the British Championships over three miles in London four days later.

– I also told him I couldn’t guarantee a good result on 7 July since it was the day after the race in Stockholm – but I could run.

– On the other hand, I said that if he could arrange a race one week after London, I could guarantee a world record over 10,000 metres.

Mother-in-Law Passed Away

– We stayed in contact by phone over the following days, but he kept trying to get me to run 5,000 metres.

– He had made agreements with Bob Schul (Olympic champion over 5,000 metres in 1964) and Billy Mills (Olympic champion over 10,000 metres in 1964) to meet me – but not at a distance longer than 5,000 metres.

– I insisted that I wanted to run 10,000 metres, and if that couldn’t be arranged, I considered returning home to Australia—also because my mother-in-law was seriously ill.

– In early July, we were informed that she was so ill that she probably wouldn’t survive until our planned return, so my wife rushed back to Australia.

– She insisted that I stay behind and do the job. Just two days after she got home, her mother passed away, and the world record I set over three miles in London was in her honour.

Missing One Runner

– After the race in London, I wanted to go home, but Arne had now built an entire meet in Oslo around me.

– Helen said that since Arne had put so much work into it, I had to show up. And I could still fulfil the dream of a new world record over 10,000 metres.

– You can therefore imagine my disappointment when Jimmy Hogan and I arrived in Oslo, only to discover that no one else wanted to run.

– I knew I could break the world record, but according to the rules, at least three runners had to start and finish the race.

– Arne showed me the programme for the meet, with only Jimmy and me on the start list – but with space for one more name.

– But that space was empty. There were just dots there.

– At that moment, I was desperate. I had persuaded Jimmy, who had won the British championship over six miles, to come. But we needed one more runner. The hunt was on.

Danish Rescue

– There was a campsite not far from Bislett, and Jim and I jogged through it in an attempt to find a long-distance runner who might have come to watch the meet but could be persuaded to run instead.

– After trying to talk to a couple of joggers who didn’t understand a word of what we were saying, we met a Dane who said, “That’s fine. I’ll do it”. His name was Claus Børsen.

– I told him the only thing that mattered was that he finished – and that he had to finish. Otherwise, the record wouldn’t be ratified, and everything would be wasted.

– That was my nightmare – that I would break the record, only to see him drop out.

Carried Along

– But Børsen did the job, even though I was worried.

– My memories from that record night are first and foremost of the crowd (17,500 were present), who carried me around the stadium with their enthusiastic applause. You could literally feel the tension among the spectators. I think that mixed with the fact that I knew I was running well under the schedule I had set for 28 minutes.

– I remember wondering just how fast I could run. At one point, I was even ahead of a 27:30 pace. It was a very special experience to feel what I call “The Flow” – when the mind and body are working perfectly together.

Clarke finished in 27:39.89, or 27:39.4 as the official hand time, after setting a world record for six miles en route at 26:47.0. Jim Hogan finished in 29:19.6, while Børsen was timed at 31:03.2.

As a small curiosity, it can be mentioned that Svein Arne Hansen – who took over as the “Bislett general” after Haukvik and later became president of both the Norwegian Athletics Federation and European Athletics – was the starter assistant for the field.

Eighteen Records

In total, Clarke set 18 world records at various distances during his career, including four over 5,000 metres and two over 10,000 metres. His best championship result was an Olympic bronze medal over 10,000 metres in 1964.

Could Have Run Faster

– How do I rank the 10,000 metres race in Oslo?

– I never really got the chance to run many 10,000 metres at major meets, because organisers thought such a long race was too boring. But I think I may have run a better race in London ahead of the 1968 Olympics. I ran 27:49.4 under extreme wind conditions.

– Had the wind been normal, I think I would have run under 27:20 – perhaps even close to 27 minutes. But we’ll never know.

– There was another perfect thing about running in Scandinavia.

– It rarely blew the way it could elsewhere.

Unique Bislett

– There are two reasons why so many records have been set at Bislett.

– The atmosphere and the enthusiasm you feel when you compete.

– The Bislett crowd is the most knowledgeable audience in the athletics circuit. They understand what is happening before it has to be explained.

– Where other crowds cheer when they are told what has happened, the crowd at Bislett cheers while it is happening. I just hope this is something that will live on – because if it does, there is no better track to compete on anywhere in the world.

By Morten Olsen